The weather forecast boded ill: 90% chance of rain, all day. Monday, May 27th followed a particularly schizophrenic weather week in the Black Hills of South Dakota that had included 60’s and sunny, a foot of snow, flooding, hail, and buckets of rain followed by barrels of mud.

We had raised the 800 flags in the annual Freedom Field at the Sturgis Buffalo Chip the prior Friday, an emotionally stirring start to Memorial Day Weekend, that time specifically set aside to honor those lost while fighting for our country. The weekend would be capped by the inaugural Buffalo Chips Memorial Ride, a group ride to a humble monument near Reva, SD, about 90 miles north of the Chip, where Jonathan “Buffalo Chips” White, a U.S. Army Scout, loyal follower of Buffalo Bill Cody, and the campground’s namesake is buried. Some, including General Philip Sheridan, said White followed Cody too closely, hence the nickname conferred by Sheridan: Buffalo Chips White.

People often assume that Buffalo Chip Campground owner Rod Woodruff named the place on a whim, but it was more intentional – and serendipitous – than that. See, American pioneer heritage surrounds this part of western South Dakota: in 1874, General Custer’s expedition camped less than a mile from the present-day Buffalo Chip and if you climb Bear Butte, a legacy place sacred to Native Americans just to the north, you can still see the wagon train ruts that remain along the Deadwood to Bismarck Trail.

As for Buffalo Chips White, certain detail is lost to history but wide brushstrokes paint the story this way: When the Civil War ended, White, who’d lived in the South and fought for the Confederacy, headed West to seek his fortune. His scouting skills earned him notice and broadened his friendships among other trailblazers, including Bill Cody, whom he emulated. Some reports have credited White with saving Cody’s life once.

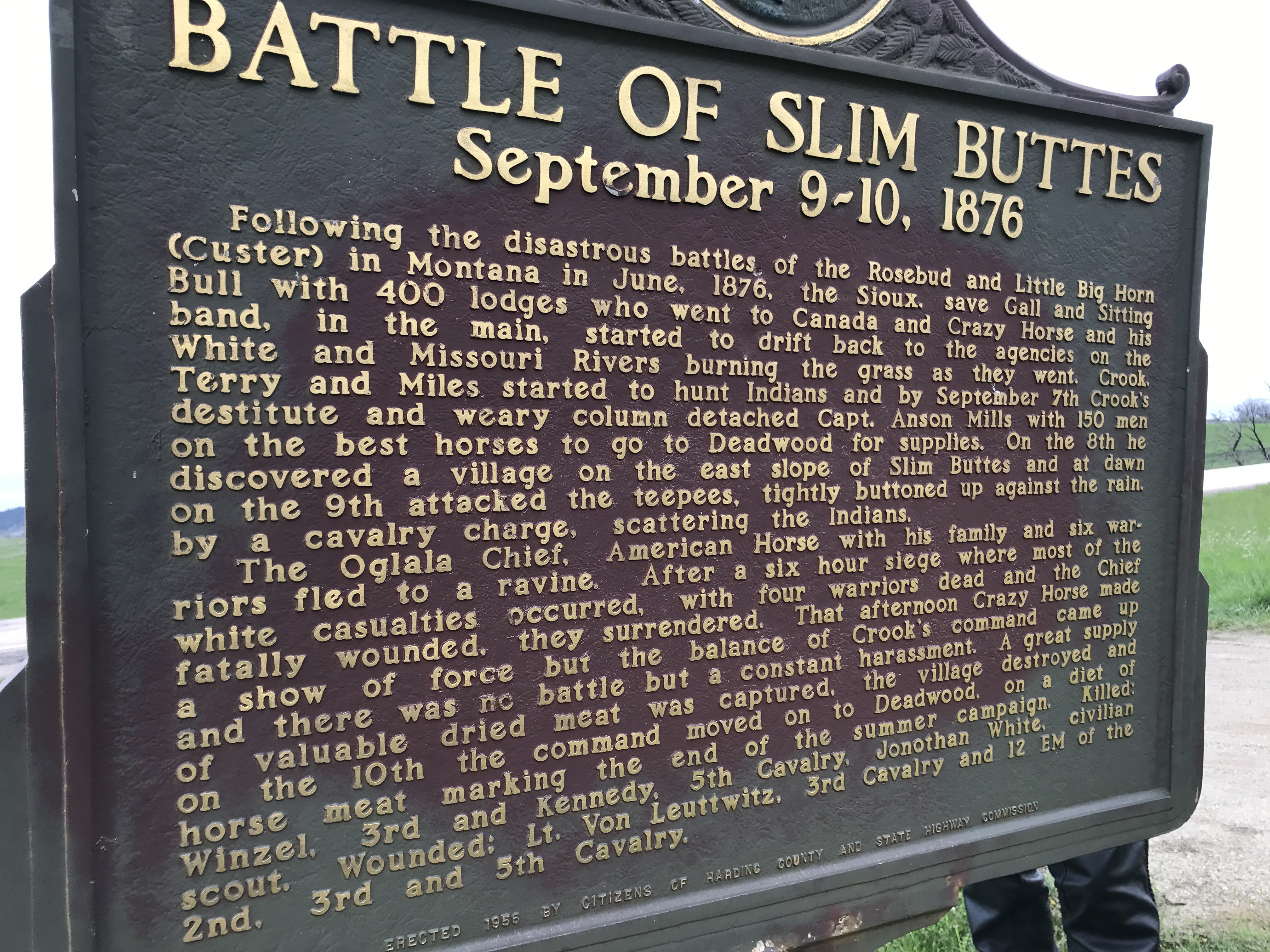

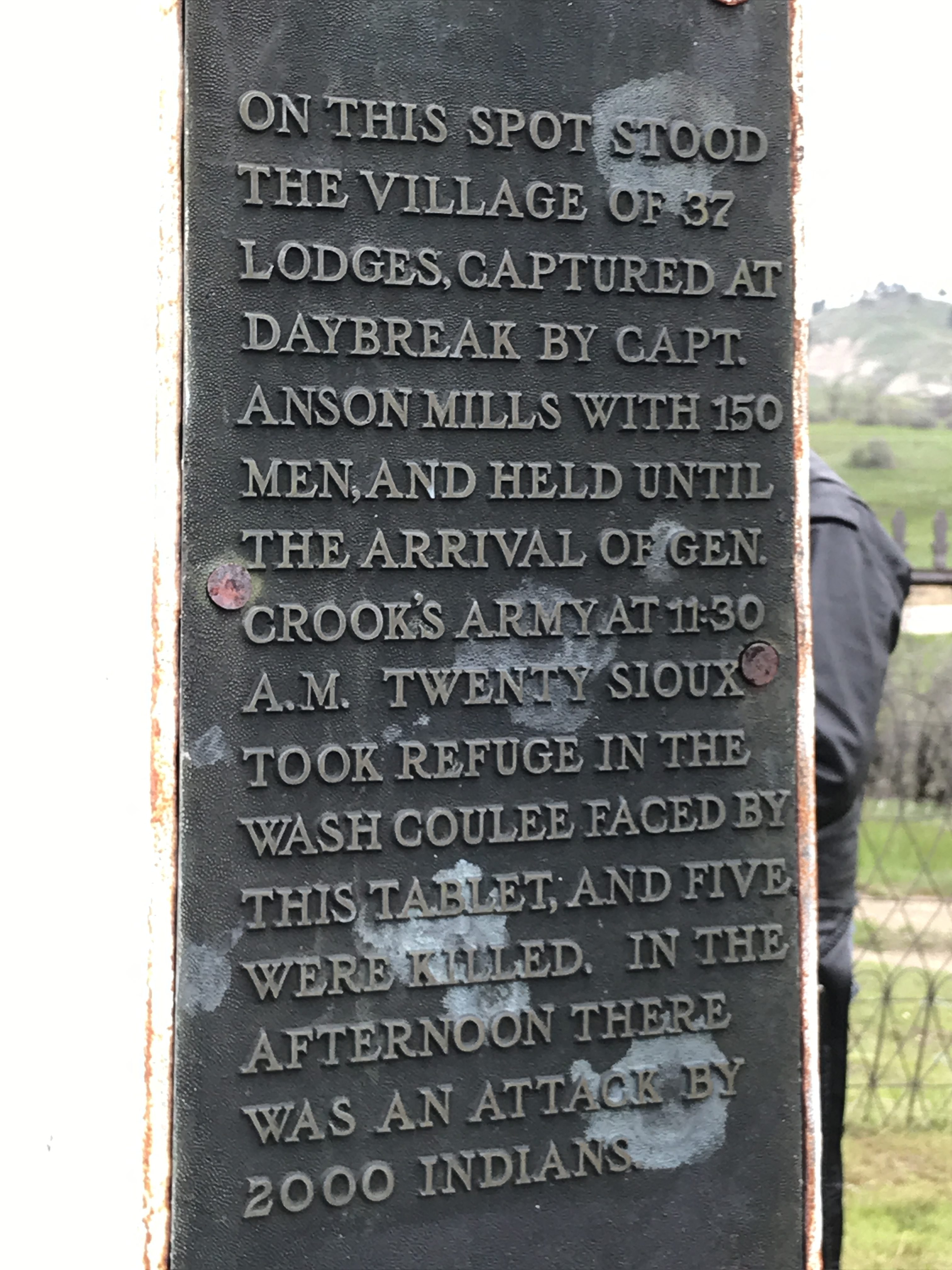

By the autumn of 1876, Buffalo Chips was a civilian scout with an Army contingent led by General George Crook, who was charged with hunting down Native American bands that September, three months after the Battle of Little Big Horn. On September 9th, Crook got word that Captain Anson Mills, who Crook had sent to Deadwood for much-needed supplies, had captured a Lakota village consisting of 37 lodges near Slim Buttes. Mills requested assistance, as a counter assault was expected.

When Crook, White and soldiers from the 2nd, 3rd and 5th Cavalries, arrived to assist Mills and his men, they were already under attack by Crazy Horse’s warriors, led by Oglala Chief American Horse. An estimated 800 Native American warriors were vanquished by Crook’s forces of about 2,000 on September 10, 1876 in what was named the Battle of Slim Buttes.

Along with a vast amount of dried meat, ammunition and other provisions, the victors recovered items from the Battle of Little Bighorn among the village tipis, including a 7th Cavalry Regiment flag in the lodge of Chief American Horse, Captain Myles Keogh’s bloody gauntlets, and personal items of other soldiers killed in that battle.

The Battle of Slim Buttes was not without casualties; Americans killed there were Army Scout Jonathan “Buffalo Chips” White and Private John Winzel (or Wenzel) of the 3rd Cavalry. Private Edward Kennedy of the 5th Cavalry died from wounds he sustained in the battle. The Slim Buttes Battlefield Monument, dedicated in 1920, recognizes these three.

Chief American Horse was also mortally wounded in the skirmish and died several days later. Slim Buttes became the first U.S. Army victory in the Great Sioux War of 1876.

So on a cold Memorial Day 2019, as fog obliterated visibility and rain loomed certain, a small group of motorcyclists rode 90 miles north of the Sturgis Buffalo Chip to honor brave soldiers good and true such as Jonathan White. Soldiers who stand as testaments to loyalty, steadfast friendship, unyielding courage, and pioneer spirit – characteristics that bikers generally and Buffalo Chip campers specifically hold dear.

Join us next Memorial Day when we’ll do it once again.

Our thanks to the following friends whose western prairie hospitality made the ride warmer, richer in history, and just plain better:

Reva Store

Joe and Karen Wilkinson

Box 96, 14759 SD Highway 20

Reva, SD 57651

605-375-3633, 605-866-443

Hoover General Store & Community Center

Leona McFarland, Jean and Jerry McNulty

15820 Hoover Rd

Newell, SD 57760

605-866-4690, 605-866-4436

Spur Creek Saloon & Ranch

Robert & Becky Boylan

17698 SD Highway 79

Newell, SD 57760

605-391-8282

Placed ½ mile northwest of the actual battle site, Slim Buttes Monument is located on SD Highway 20, ¼ mile west of the intersection with SD Highway 79 and 1 mile west of Reva, SD.

Postscript:

A description of White’s demise appears on a blog titled The First Scout written by Dakota Wind. Included are additional details of the Battle of Slim Buttes, from an account written three months after the battle by a contemporary identified only as “Fintery” who refers to White as “Charley.”

http://thefirstscout.blogspot.com/2011/05/war-correspondence-from-front-lines.html

“Diagonally the opposite, on the northern slope, lay the stalwart remains of Charley White – “Buffalo Chip,” as he was called – the champion harmless liar and most genial scout upon the plains. I saw him fall and heard his death cry. Anxious to distinguish himself, he crept cautiously up the slope to have a shot at the hostiles. Some of the soldiers shouted, “Get away from there Charley, they’ve got a bead on you!” Just then a shot was fired, which broke the thigh bone of a soldier of the 5th Cavalry, named Kennedy, and White raised himself on his hands and knees in order that he might locate the spot from whence the bullet came. As he did so, one of the besieged Indians, quick as lightning, got his range and shot him squarely through the left nipple. Charley threw up his hands, crying out loud enough for all of us to hear him, “My God, my God, boys, I’m done for this time!” One mighty convulsion doubled up his body, then he relaxed all over and rolled like a log three or four feet down the slope. His dead face expressed tranquility rather than agony when I looked at him some hours later. The wind blew the long, fair locks over the cold features, and eyes were almost perfectly closed. The slain hunter looked as if he were taking a rest after a toilsome buffalo chase.”

More Stories

Announcing Two Days of Crazy A$$ Stunts at the Sturgis Buffalo Chip

Don’t Miss the Big One! Sturgis Buffalo Chip 2025

HARLEY-DAVIDSON HOMECOMING FESTIVAL WILL REV AND ROCK MILWAUKEE JULY 10-13