Story and Photos by ITN European Reporter Herve’ Rebollo

Salut à toi American rider,

Long time I wanted to see in real the sadly legendary V-1.

On this early first Saturday morning of September it was time to get back on the road … I was not really in good mood, the sky was gray and the weather an alternance of sunny / rainy periods … anyway, lets go!! But yes, it was not my day. After 50 miles, I realize I have forgot my wallet in my living room … Sh…!!! Ok, u-turn and way back home. Means that two hours after having leaving home I was at … 50 miles of my house … and yes, It was not my day, totally wet under a crazy rain. Because I was such in a bad mood that I decided not to wear my rain suit. Real riders have dirty bikes and strongly smell wet leather.

On this early first Saturday morning of September it was time to get back on the road … I was not really in good mood, the sky was gray and the weather an alternance of sunny / rainy periods … anyway, lets go!! But yes, it was not my day. After 50 miles, I realize I have forgot my wallet in my living room … Sh…!!! Ok, u-turn and way back home. Means that two hours after having leaving home I was at … 50 miles of my house … and yes, It was not my day, totally wet under a crazy rain. Because I was such in a bad mood that I decided not to wear my rain suit. Real riders have dirty bikes and strongly smell wet leather.

Finally, I join my first stage for my traditional coffee break: the old city of Gisors and its marvelous castle. The Château de Gisors is a castle in the department of Eure. The castle was a key fortress of the Dukes of Normandy in the 11th and 12th centuries. It was intended to defend the Anglo-Norman Vexin territory from the pretensions of the King of France.

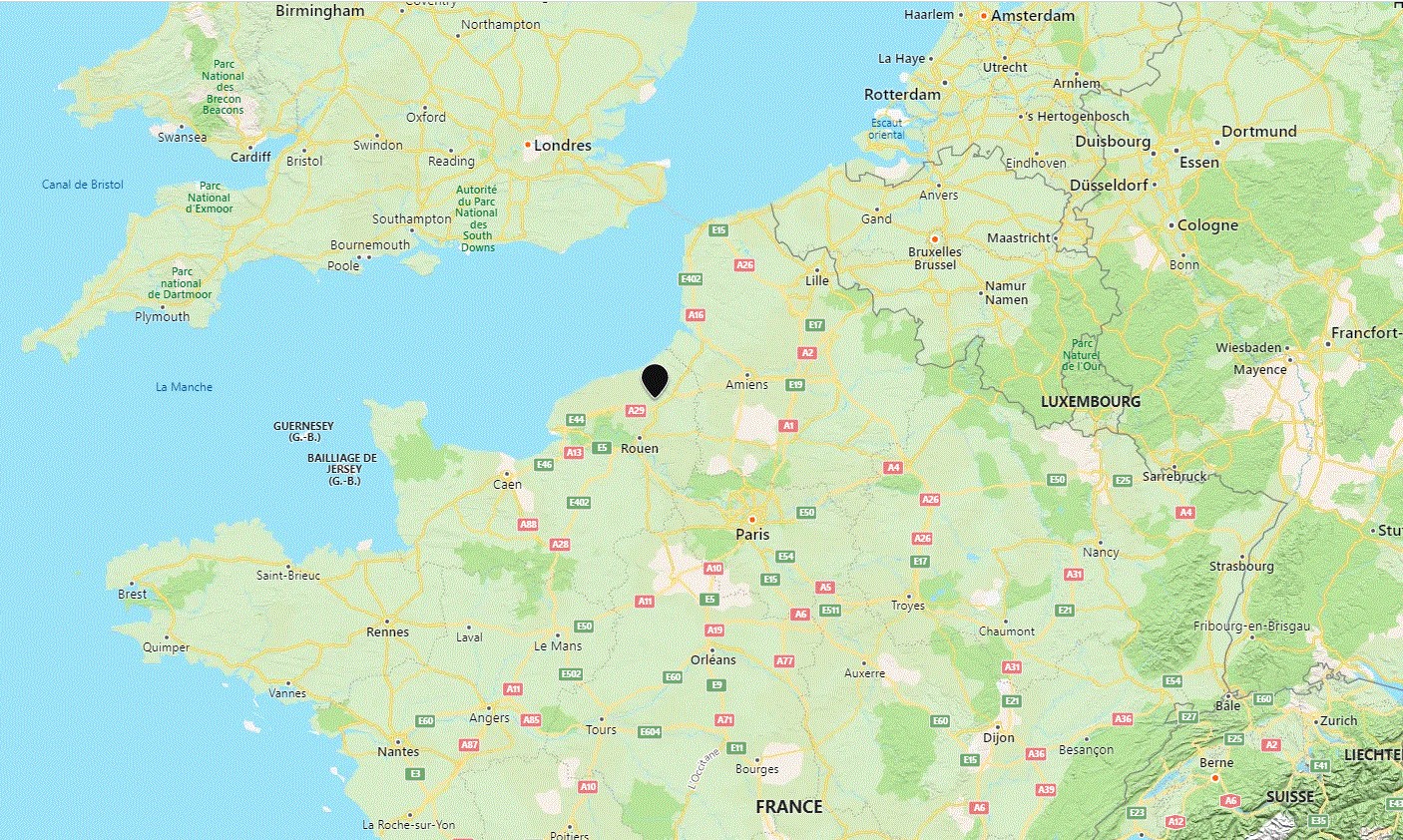

But the main target of this new road trip was another historical site (of the WWII), 150 miles after Gisors: the most preserved site of V-1 flying bomb in France (unic world-wide) located in the middle of nowhere in Val Ygot, near Ardouval in Normandy (I’m 248,45% sure you don’t know this place).

But the main target of this new road trip was another historical site (of the WWII), 150 miles after Gisors: the most preserved site of V-1 flying bomb in France (unic world-wide) located in the middle of nowhere in Val Ygot, near Ardouval in Normandy (I’m 248,45% sure you don’t know this place).

I was really excited because I knew there was still a real V-1 model on display.

I was really excited because I knew there was still a real V-1 model on display.

The V-1 flying bomb (German: Vergeltungswaffe 1 “Vengeance Weapon 1”), also known to the Allies as the buzz bomb, or doodlebug, and in Germany as Kirschkern (cherry stone) or Maikäfer (maybug), as well as by its official RLM aircraft designation of Fi 103 was an early cruise missile and the only production aircraft to use a pulsejet for power. The V-1 was the first of the so-called “Vengeance weapons” series deployed for the terror bombing of London. Because of its limited range, the thousands of V-1 missiles launched into England were fired from launch facilities along the French and Dutch coasts. The Wehrmacht first launched the V-1s against London on 13 June 1944, one week after (and prompted by) the successful Allied landing in France. At peak, more than one hundred V-1s a day were fired at southeast England, 9,521 in total, decreasing in number as sites were overrun until October 1944, when the last V-1 site in range of Britain was overrun by Allied forces. After this, the Germans directed V-1s at the port of Antwerp and at other targets in Belgium, launching a further 2,448 V-1s. The attacks stopped only a month before the war in Europe ended, when the last launch site in the Low Countries was overrun on 29 March 1945.

The V-1 flying bomb (German: Vergeltungswaffe 1 “Vengeance Weapon 1”), also known to the Allies as the buzz bomb, or doodlebug, and in Germany as Kirschkern (cherry stone) or Maikäfer (maybug), as well as by its official RLM aircraft designation of Fi 103 was an early cruise missile and the only production aircraft to use a pulsejet for power. The V-1 was the first of the so-called “Vengeance weapons” series deployed for the terror bombing of London. Because of its limited range, the thousands of V-1 missiles launched into England were fired from launch facilities along the French and Dutch coasts. The Wehrmacht first launched the V-1s against London on 13 June 1944, one week after (and prompted by) the successful Allied landing in France. At peak, more than one hundred V-1s a day were fired at southeast England, 9,521 in total, decreasing in number as sites were overrun until October 1944, when the last V-1 site in range of Britain was overrun by Allied forces. After this, the Germans directed V-1s at the port of Antwerp and at other targets in Belgium, launching a further 2,448 V-1s. The attacks stopped only a month before the war in Europe ended, when the last launch site in the Low Countries was overrun on 29 March 1945.

Lucky me, when arriving on the site the weather was perfect, I was absolutely alone, the place beautiful and, surprisingly, so peaceful.

Lucky me, when arriving on the site the weather was perfect, I was absolutely alone, the place beautiful and, surprisingly, so peaceful.

Other surprise: even 76 years later it is asked you to keep your feet on the trail …

Other surprise: even 76 years later it is asked you to keep your feet on the trail …

Welcome to the Val Ygot, site of V-1!

Welcome to the Val Ygot, site of V-1!

And now, let me tell you a very interesting story about a modest WW2 resistance hero and the V-1 flying bomb, at Val Ygot: Michel HOLLARD.

And now, let me tell you a very interesting story about a modest WW2 resistance hero and the V-1 flying bomb, at Val Ygot: Michel HOLLARD.

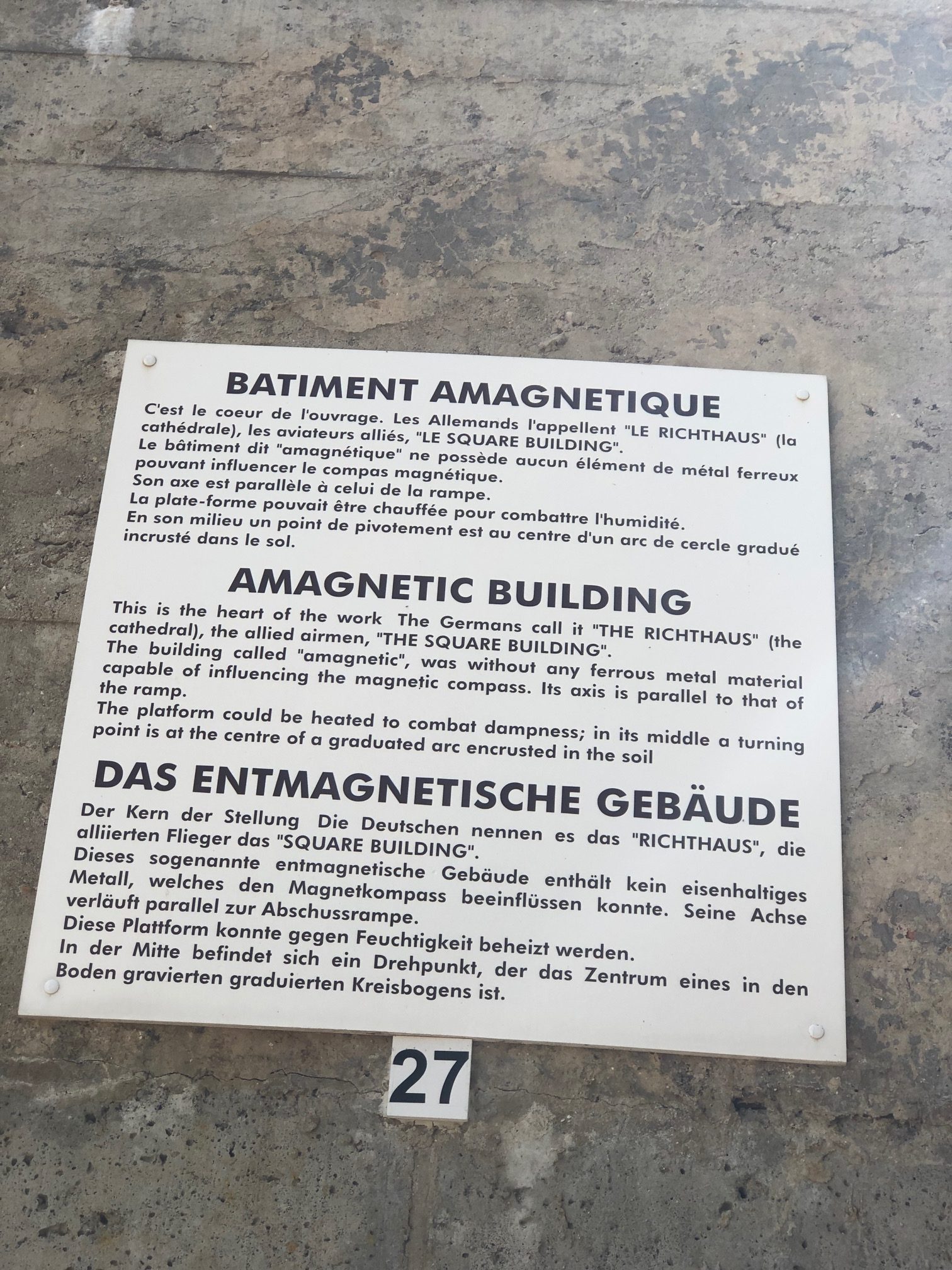

In the summer of 1943, a middle aged Frenchman in blue overalls pushed a wheelbarrow past German sentries into a construction site at Bonnetot, between Dieppe and Rouen in Normandy. The man, Michel Hollard, did not look extraordinary but he was. Audacious and brave, Michel’s actions that day would go on to save many thousands of lives. The building site was not close to any railway lines and away from the coast and its purpose was not clear. Michel knew from his contacts this was one of many similar sites being built in northern France. Looking around he saw a number of single floor buildings connected by cement paths. Blue rope was being used to mark new tracks that stood alone. Intrigued, Michel bent down as if to tie a shoelace and discretely lay a compass on the ground. He noted the direction of the blue rope. Calmly he then left the site and made his way back to Paris. Back in his apartment Michel took out a map of northern France and southern England. Using the coordinates what he saw worried him very much indeed. The tracks were clearly aimed at London.

In the summer of 1943, a middle aged Frenchman in blue overalls pushed a wheelbarrow past German sentries into a construction site at Bonnetot, between Dieppe and Rouen in Normandy. The man, Michel Hollard, did not look extraordinary but he was. Audacious and brave, Michel’s actions that day would go on to save many thousands of lives. The building site was not close to any railway lines and away from the coast and its purpose was not clear. Michel knew from his contacts this was one of many similar sites being built in northern France. Looking around he saw a number of single floor buildings connected by cement paths. Blue rope was being used to mark new tracks that stood alone. Intrigued, Michel bent down as if to tie a shoelace and discretely lay a compass on the ground. He noted the direction of the blue rope. Calmly he then left the site and made his way back to Paris. Back in his apartment Michel took out a map of northern France and southern England. Using the coordinates what he saw worried him very much indeed. The tracks were clearly aimed at London.

Michel was a fierce patriot. Born 10 July 1898 near Paris, he ran away from home at 16 to join the French army fighting the German invasion of 1914. During the terrible years of WW1 he rose in the ranks to infantry officer and for valour was awarded the Croix de Guerre. After the war he trained as an engineer, married and became the proud father of three children. Michel had tried to join up at the beginning of the war in 1939 but had been told he was too old. As the German army marched into Paris he had taken his family south. He could have remained there, uneasy but safe, working in his company’s head office, but then he discovered the company would be supplying armaments to the German army: he resigned and took a job with the Dijon gasogenic factory making cars fuelled with wood gas. The gas was extracted from wood or charcoal and this fuel was sourced from across France and Switzerland. This gave Michel an idea. Travel was something the occupying army did not generally encourage, but he knew enough about the business to pretend to be a buyer sourcing fuel.

Michel was a fierce patriot. Born 10 July 1898 near Paris, he ran away from home at 16 to join the French army fighting the German invasion of 1914. During the terrible years of WW1 he rose in the ranks to infantry officer and for valour was awarded the Croix de Guerre. After the war he trained as an engineer, married and became the proud father of three children. Michel had tried to join up at the beginning of the war in 1939 but had been told he was too old. As the German army marched into Paris he had taken his family south. He could have remained there, uneasy but safe, working in his company’s head office, but then he discovered the company would be supplying armaments to the German army: he resigned and took a job with the Dijon gasogenic factory making cars fuelled with wood gas. The gas was extracted from wood or charcoal and this fuel was sourced from across France and Switzerland. This gave Michel an idea. Travel was something the occupying army did not generally encourage, but he knew enough about the business to pretend to be a buyer sourcing fuel.

Having created a reason to travel, however false, Michel carefully started to build a network of like-minded people. His network was made up of ordinary people, many of them railway workers. Independent from other resistance networks, Michel’s network had no name until after the war when it would become known as Réseau AGIR (Agir means ‘to act’ in French). Michel and his agents began to record everything about the enemy occupiers they saw; German troop movements, factory contracts, new buildings, overheard conversations. Michel’s next move was to find a way to speak the British and tell them about his very well placed network. He would have to travel across the forbidden zone.

Having created a reason to travel, however false, Michel carefully started to build a network of like-minded people. His network was made up of ordinary people, many of them railway workers. Independent from other resistance networks, Michel’s network had no name until after the war when it would become known as Réseau AGIR (Agir means ‘to act’ in French). Michel and his agents began to record everything about the enemy occupiers they saw; German troop movements, factory contracts, new buildings, overheard conversations. Michel’s next move was to find a way to speak the British and tell them about his very well placed network. He would have to travel across the forbidden zone.

With a permit to travel to the east of France in search of charcoal supplies, Michel made plans to cross over into Switzerland and make contact with the British embassy in Bern. After an unsuccessful first attempt he made for Morteau in the forbidden zone about 10km from the Swiss border. Nearing the border he finds a saw mill and after watching for a while decides to introduce himself to the owner. His instincts are good. César Gaiffe is keen to help and takes him to meet local carter Paul Cuenot who agrees to take Michel close to the frontier. Slowly the cart with Paul and Michel rolls towards an alpine pasture. At the edge of the pasture he slides from the cart and runs down the valley and across a small brook. The way looks clear but the Germans are known to take shots at people escaping into Switzerland across the meadow. Hiding by a wall he waits for darkness. Then he walks. It is 22 May 1941. Now in Switzerland, Michel follows a road and soon reaches the Swiss customs post. He hands over his identity card. The official asks what business he has in Switzerland. ‘Family business.’ ‘I’m going to Berne’. He could face arrest, he could be turned away. But the official simply takes his ID card and tells him it will be returned when he comes back. And so Michel Hollard walks the 80km to Bern.

With a permit to travel to the east of France in search of charcoal supplies, Michel made plans to cross over into Switzerland and make contact with the British embassy in Bern. After an unsuccessful first attempt he made for Morteau in the forbidden zone about 10km from the Swiss border. Nearing the border he finds a saw mill and after watching for a while decides to introduce himself to the owner. His instincts are good. César Gaiffe is keen to help and takes him to meet local carter Paul Cuenot who agrees to take Michel close to the frontier. Slowly the cart with Paul and Michel rolls towards an alpine pasture. At the edge of the pasture he slides from the cart and runs down the valley and across a small brook. The way looks clear but the Germans are known to take shots at people escaping into Switzerland across the meadow. Hiding by a wall he waits for darkness. Then he walks. It is 22 May 1941. Now in Switzerland, Michel follows a road and soon reaches the Swiss customs post. He hands over his identity card. The official asks what business he has in Switzerland. ‘Family business.’ ‘I’m going to Berne’. He could face arrest, he could be turned away. But the official simply takes his ID card and tells him it will be returned when he comes back. And so Michel Hollard walks the 80km to Bern.

Much later that day a very tired, dirty and dishevelled Michel Hollard presents himself to Brigadier Cartwright, the British embassy military attaché in Bern. As a show of goodwill he has with him information on France’s automotive manufacturing capabilities. Suspicious that anyone could find their way over the tightly controlled border and unimpressed by Michel’s dirty, dishevelled appearance, the Brigadier tells him coldly they ‘do not deal with spies’ and shows him the door. Michel vows to return while Brigadier Cartwright does some research into this very ordinary looking Frenchman.

Much later that day a very tired, dirty and dishevelled Michel Hollard presents himself to Brigadier Cartwright, the British embassy military attaché in Bern. As a show of goodwill he has with him information on France’s automotive manufacturing capabilities. Suspicious that anyone could find their way over the tightly controlled border and unimpressed by Michel’s dirty, dishevelled appearance, the Brigadier tells him coldly they ‘do not deal with spies’ and shows him the door. Michel vows to return while Brigadier Cartwright does some research into this very ordinary looking Frenchman.

Much later that day a very tired, dirty and dishevelled Michel Hollard presents himself to Brigadier Cartwright, the British embassy military attaché in Bern. As a show of goodwill he has with him information on France’s automotive manufacturing capabilities. Suspicious that anyone could find their way over the tightly controlled border and unimpressed by Michel’s dirty, dishevelled appearance, the Brigadier tells him coldly they ‘do not deal with spies’ and shows him the door. Michel vows to return while Brigadier Cartwright does some research into this very ordinary looking Frenchman.

Much later that day a very tired, dirty and dishevelled Michel Hollard presents himself to Brigadier Cartwright, the British embassy military attaché in Bern. As a show of goodwill he has with him information on France’s automotive manufacturing capabilities. Suspicious that anyone could find their way over the tightly controlled border and unimpressed by Michel’s dirty, dishevelled appearance, the Brigadier tells him coldly they ‘do not deal with spies’ and shows him the door. Michel vows to return while Brigadier Cartwright does some research into this very ordinary looking Frenchman.

One month later Michel returned to Bern. By now the British were very excited to see him. Trustworthy agents had vouched for his integrity and rumours of his resistance network interested them very much. The British explained what they needed to learn from occupied France and Michel began to regularly cross the border in all weather and seasons, each time bringing incredible information.

One month later Michel returned to Bern. By now the British were very excited to see him. Trustworthy agents had vouched for his integrity and rumours of his resistance network interested them very much. The British explained what they needed to learn from occupied France and Michel began to regularly cross the border in all weather and seasons, each time bringing incredible information.

During the summer of 1943 railway construction worker Jean-Henri Daudenard shared some intriguing information. The Germans were building odd structures in heavily camouflaged, often wooded sites. Particularly between Rouen and Dieppe. To gain a permit for travel Michel disguised himself as a pastor and explained to an official he would like to take bibles and religious tracts to the railway workers around Rouen. A man of great faith, his knowledge of the bible clearly impressed and he is given the permit. Taking the train from Rouen he changes into blue overalls and a workman’s hat and, arriving at Auffay, explores every road from the station. Then near Bonnetot-le-Faubourg he sees a lot of activity. Getting closer he sees the entrance to a construction site. Picking up a discarded wheelbarrow Michel Hollard walked in.

During the summer of 1943 railway construction worker Jean-Henri Daudenard shared some intriguing information. The Germans were building odd structures in heavily camouflaged, often wooded sites. Particularly between Rouen and Dieppe. To gain a permit for travel Michel disguised himself as a pastor and explained to an official he would like to take bibles and religious tracts to the railway workers around Rouen. A man of great faith, his knowledge of the bible clearly impressed and he is given the permit. Taking the train from Rouen he changes into blue overalls and a workman’s hat and, arriving at Auffay, explores every road from the station. Then near Bonnetot-le-Faubourg he sees a lot of activity. Getting closer he sees the entrance to a construction site. Picking up a discarded wheelbarrow Michel Hollard walked in.

A number of low buildings were linked by concrete paths. Separate but close by, pairs of long tracks were being laid out, guided by pegged blue string. Near the string Michel bent down, as if to tie a shoelace. He quickly placed a very small compass on the ground and noted the layout. Back home he laid out a map that showed northern France and southern England. He plotted coordinates taken in the forest and what he saw filled him with dread. The long tracks were aimed straight at London. In Michel’s carefully prepared report of September 1943 to the British Secret Intelligence Service he personally identified six sites at Bonnetot, le Faubourg, Auffray, Totes, Ribeaucourt, Maison Ponthieu and Bois Carré. It was a plan of launch pads for Hitler’s new, merciless weapon, Vergeltungswaffe 1 / V-1. .

A number of low buildings were linked by concrete paths. Separate but close by, pairs of long tracks were being laid out, guided by pegged blue string. Near the string Michel bent down, as if to tie a shoelace. He quickly placed a very small compass on the ground and noted the layout. Back home he laid out a map that showed northern France and southern England. He plotted coordinates taken in the forest and what he saw filled him with dread. The long tracks were aimed straight at London. In Michel’s carefully prepared report of September 1943 to the British Secret Intelligence Service he personally identified six sites at Bonnetot, le Faubourg, Auffray, Totes, Ribeaucourt, Maison Ponthieu and Bois Carré. It was a plan of launch pads for Hitler’s new, merciless weapon, Vergeltungswaffe 1 / V-1. .

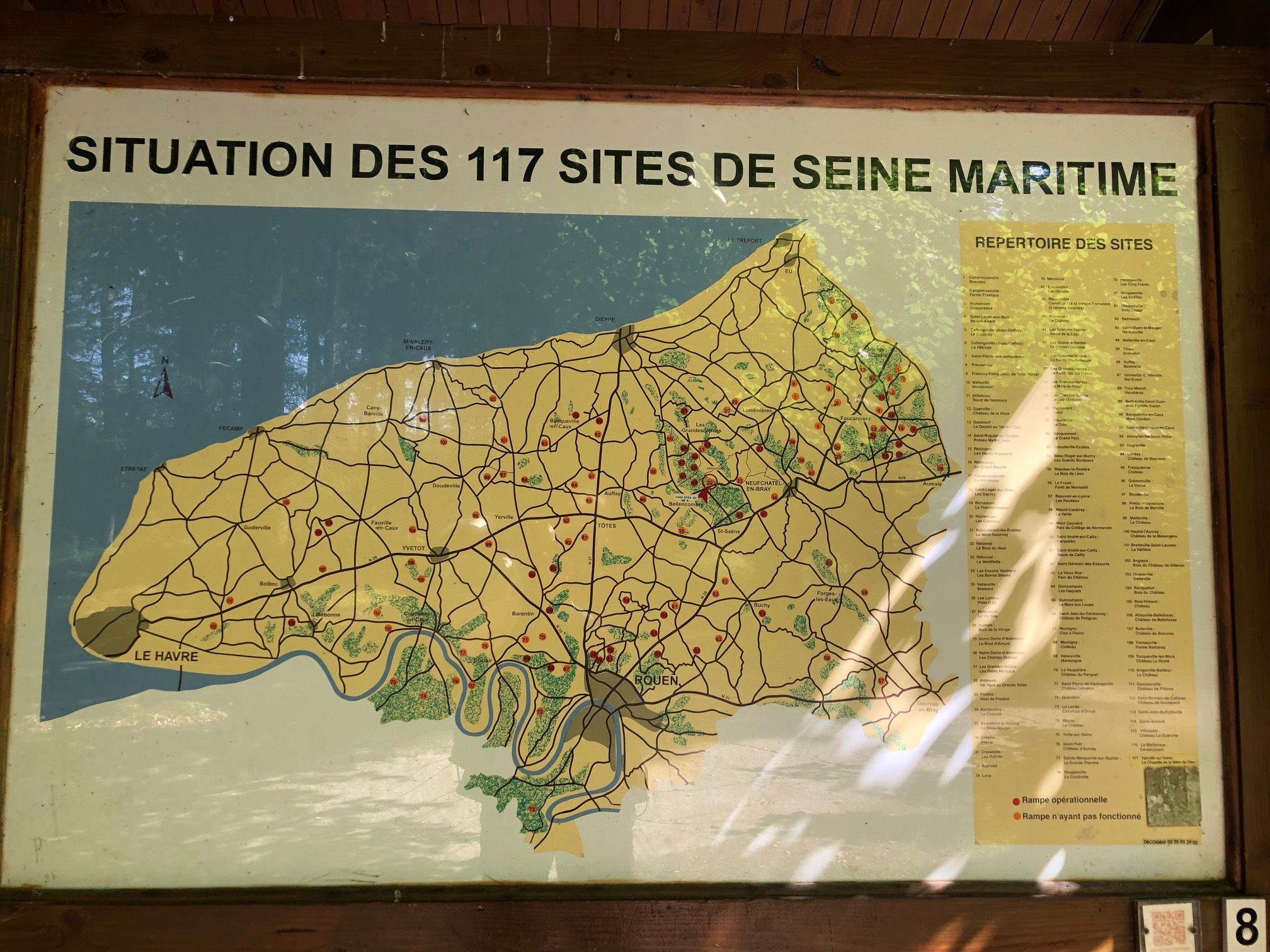

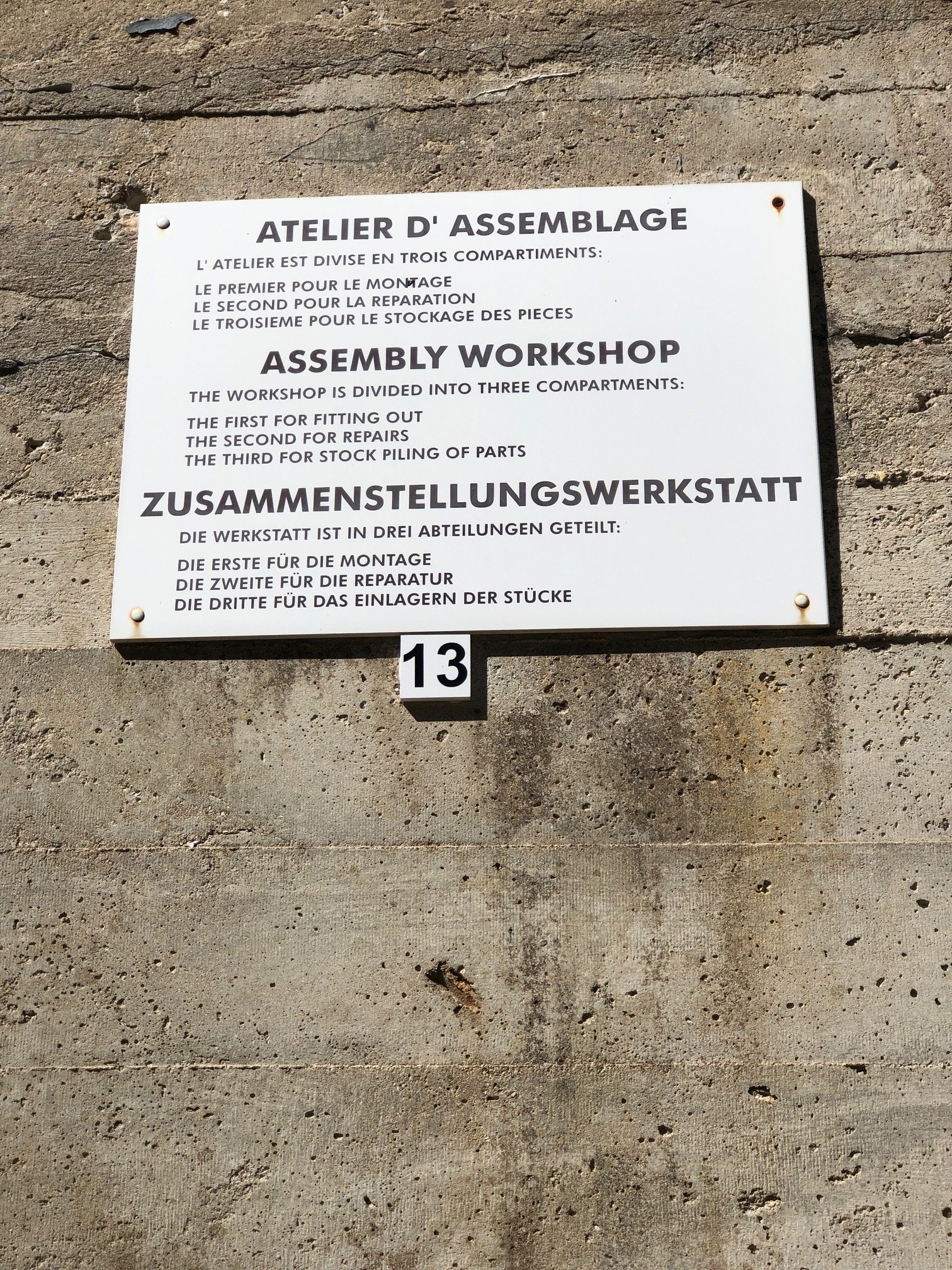

Michel arranged for a young engineer André Comps to be given the job of draughtsman at the Picardy Bois Carré construction site. André managed to make a plan of every building under construction. He even managed to make a copy of plans for the base and rails of what were clearly launch ramps, by taking the drawing from the coat pocket of a German contractor when he hung it up to go to the toilet. Michel and four comrades then bicycled from Pas-de-Calais to Cherbourg searching for exact locations of the sites. In the first 3 weeks they discover more than 60 buildings. By mid-November they have found more than 100. Michel smuggles the information to the British Military attaché in Berne.

Michel arranged for a young engineer André Comps to be given the job of draughtsman at the Picardy Bois Carré construction site. André managed to make a plan of every building under construction. He even managed to make a copy of plans for the base and rails of what were clearly launch ramps, by taking the drawing from the coat pocket of a German contractor when he hung it up to go to the toilet. Michel and four comrades then bicycled from Pas-de-Calais to Cherbourg searching for exact locations of the sites. In the first 3 weeks they discover more than 60 buildings. By mid-November they have found more than 100. Michel smuggles the information to the British Military attaché in Berne.

Knowing the British were desperate for information about the weapon to be used at the precise new sites across northern France, Michel’s network was on high alert. News came back from national railway company worker André Bouguet that an unusual amount of rail transport was going north from Rouen. It was all destined for the goods yard at Auffay, close to the new construction site at Bonnetot-le-Faubourg. Inside the shed under tarpaulin he found all the parts to a top secret weapon. He measured and drew what he saw, then made the perilous journey back to Switzerland. Rumours of a secret weapon being developed by the Nazi’s was already worrying British intelligence when Michel’s information reached them in London. They saw how similar Michel’s drawings were to single bomb found crashed in Denmark in August that year. The Royal Air Force (RAF) stepped up reconnaissance of the area. Then in December 1943 Churchill instigates Operation Crossbow and the the RAF begin bombing, very precisely, launch sites across northern France. When the network got word back that a senior German rocket scientist was staying at a certain chateau, it was bombed within five hours of the intelligence reaching London.

Knowing the British were desperate for information about the weapon to be used at the precise new sites across northern France, Michel’s network was on high alert. News came back from national railway company worker André Bouguet that an unusual amount of rail transport was going north from Rouen. It was all destined for the goods yard at Auffay, close to the new construction site at Bonnetot-le-Faubourg. Inside the shed under tarpaulin he found all the parts to a top secret weapon. He measured and drew what he saw, then made the perilous journey back to Switzerland. Rumours of a secret weapon being developed by the Nazi’s was already worrying British intelligence when Michel’s information reached them in London. They saw how similar Michel’s drawings were to single bomb found crashed in Denmark in August that year. The Royal Air Force (RAF) stepped up reconnaissance of the area. Then in December 1943 Churchill instigates Operation Crossbow and the the RAF begin bombing, very precisely, launch sites across northern France. When the network got word back that a senior German rocket scientist was staying at a certain chateau, it was bombed within five hours of the intelligence reaching London.

Michel Hollard and his network continued to gather information until 5 February 1944. On that day, unknowingly betrayed by a double agent, he was sitting in a café near Paris Gare du Nord station with 4 resistance comrades when they were arrested. The Gestapo interrogated him, starved him, used intense water torture and violence but Michel refused to give up a single name. Initially sentenced to death, Michel experienced appalling imprisonment including forced labour at the Neuengamme concentration camp in Germany, but survived. On liberation Michel spent some months in hospital in Switzerland. In May 1945 King George VI of England travelled to Switzerland and met Michel. He awarded him the Distinguished Service Order. The DSO citation stated: Hollard, at great personal risk, reconnoitred a number of heavily guarded V-1 sites and reported on them with such clarity that models were constructed which enabled effective bombing to be carried out. Michael was also awarded the Légion d’Honneur and the British army gave him the rank of Colonel. Michel never fully recovered from his injuries, but he was able to return to the modest life of family and work, that he had fought so hard for. Then, like many others who fought the silent war, particularly those who did it their own way, Michel Hollard was rather forgotten. He died in 1993 at the age of 95.

Michel Hollard and his network continued to gather information until 5 February 1944. On that day, unknowingly betrayed by a double agent, he was sitting in a café near Paris Gare du Nord station with 4 resistance comrades when they were arrested. The Gestapo interrogated him, starved him, used intense water torture and violence but Michel refused to give up a single name. Initially sentenced to death, Michel experienced appalling imprisonment including forced labour at the Neuengamme concentration camp in Germany, but survived. On liberation Michel spent some months in hospital in Switzerland. In May 1945 King George VI of England travelled to Switzerland and met Michel. He awarded him the Distinguished Service Order. The DSO citation stated: Hollard, at great personal risk, reconnoitred a number of heavily guarded V-1 sites and reported on them with such clarity that models were constructed which enabled effective bombing to be carried out. Michael was also awarded the Légion d’Honneur and the British army gave him the rank of Colonel. Michel never fully recovered from his injuries, but he was able to return to the modest life of family and work, that he had fought so hard for. Then, like many others who fought the silent war, particularly those who did it their own way, Michel Hollard was rather forgotten. He died in 1993 at the age of 95.

V-1s caused the destruction of over 80,000 homes in Britain between June and September 1944, but British air raids destroyed nine V-1 sites, badly damaged 35 and partially damaged another 25 out of the 104 located in the North of France across North-Eastern Normandy to the Strait of Dover. General Eisenhower said that if the V-1 sites had not been discovered and so many destroyed, Operation Overlord, D-Day, would have been impossible. Sir Brian Horrocks, regarded as one of the most successful generals of WW2, called Michel Hollard “the man who literally saved London”.

V-1s caused the destruction of over 80,000 homes in Britain between June and September 1944, but British air raids destroyed nine V-1 sites, badly damaged 35 and partially damaged another 25 out of the 104 located in the North of France across North-Eastern Normandy to the Strait of Dover. General Eisenhower said that if the V-1 sites had not been discovered and so many destroyed, Operation Overlord, D-Day, would have been impossible. Sir Brian Horrocks, regarded as one of the most successful generals of WW2, called Michel Hollard “the man who literally saved London”.

After having discover the story of this Hero, I felt so … little in this great Normandian forest …

After having discover the story of this Hero, I felt so … little in this great Normandian forest …

It was time to get back home riding across the beautiful French campaign …

It was time to get back home riding across the beautiful French campaign …

After such an experience at Val Ygot, meeting this forgotten Hero and facing the beauty of our traditional villages my bike was overwhelmed by the emotion and needed a short stop on the shoulder of the road. This is the only objective explanation I found for its reaction when it decided (yes my bike has a personal life) to break for the third time int two months (yes I know, I should go to the workshop) the support bar of its left bag … (yes, it was not my day today). No problem, I’m a biker, I necessarily have a solution. And a good biker always has his tools and of course a pair of always very useful elastic extensors. Hooray, It works!!! (have you notice this two nice stickers IRON TRADER NEWS???).

After such an experience at Val Ygot, meeting this forgotten Hero and facing the beauty of our traditional villages my bike was overwhelmed by the emotion and needed a short stop on the shoulder of the road. This is the only objective explanation I found for its reaction when it decided (yes my bike has a personal life) to break for the third time int two months (yes I know, I should go to the workshop) the support bar of its left bag … (yes, it was not my day today). No problem, I’m a biker, I necessarily have a solution. And a good biker always has his tools and of course a pair of always very useful elastic extensors. Hooray, It works!!! (have you notice this two nice stickers IRON TRADER NEWS???).

And this how I reached the marvelous Valley of the Seine river … one of the most interesting spot, for bikers, at the west of Paris …

And this how I reached the marvelous Valley of the Seine river … one of the most interesting spot, for bikers, at the west of Paris …

Once again, it was a fantastic ride (of 400 miles) in pleasant alternance of sun and rain, emotion and remembrance, culture and fun. That the life I like. Ready to share, please come to me, I’ll show you my country.

Once again, it was a fantastic ride (of 400 miles) in pleasant alternance of sun and rain, emotion and remembrance, culture and fun. That the life I like. Ready to share, please come to me, I’ll show you my country.

More Stories

RIDE TO THE GALLO-ROMAN SITE IN THE CENTER OF FRANCE

RIDE TO THE CASTLES

RIDE TO THE VALENCIA MARKET