Editor’s Note: The Donnie Smith Show brings out the best bikes – and cars – in the Midwest each spring and it reminds us that the genesis of custom motorcycling runs back to a few early pioneers. Guys like Donnie Smith, Dave Perewitz and Arlen Ness not only have talent and creativity but, equally important, they’ve had the persistence to stick with motorcycling as a business through the decades.

Here’s a look at the early years and the lifelong friendship between three of custom motorcycling’s biggest influencers – then and still.

Images courtesy of Jody Perewitz, Arlen Ness, Donnie Smith

Over the decades, custom motorcycling has seen good times and bad. Motorcycle builders have been on the top of the heap and relegated to the back alley. But for the faithful, those ingrained wrenches and riders who long ago claimed biking as their life’s work, custom motorcycles are as sublime and necessary as ever.

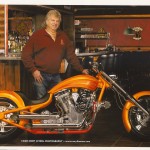

Among those few stalwarts who succeeded in the game is Donnie Smith, a man known for his custom creations not only in the Midwest but around the world. He’ll be the first to tell you that his early riding experiences didn’t exactly predict a happy life on two wheels; no, motorcycles were not his first choice. It was Uncle Elwood that got Donnie involved in bikes.

One day in the early ‘70s Elwood brought his Sportster into the drag race shop Donnie ran with his brother Happy and buddy Bob Fetrow; he wanted them to rake the bike’s neck. “We were three farm kids; we thought rake was something you did with hay,” said Donnie. Though they also had day jobs and were busy working on the Barracuda Funny Car they planned to race, they did their best for Elwood.

Soon Elwood’s friends took notice and the shop—Smith Brothers and Fetrow—started getting more bike work. A while later, when someone wanted a Springer and there were none to be found, the guys gave that a try, too. Then girders, and tanks, and fenders and so it went. After a year or so their bookkeeper said, “You know, if you got rid of that race car you could make a living out of this motorcycle thing.” So they did. Thank God for Uncle Elwood!

If you had a motorcycle business then, the way to get noticed—the only way—was to have your bikes featured in magazines. Donnie explained how SB&F first got hooked up: “The first guy that ever shot our bikes was Randy Smith from CCE. He was doing freelance for magazines in 1974. We met him in Bowling Green and he shot the bikes we were riding there. We were on cloud nine.”

Donnie also credits Bob Clark at Street Chopper for bringing attention to SB&F’s work. “He kept us out in front of people and got us to be household names.”

The next spring SB&F loaded some bikes in the van and headed to Detroit for a show called “It’s Called Detroit.” That was the first time Donnie saw Arlen Ness, though they didn’t meet till later at Tom Rudd’s Drag Specialties show in Minneapolis. But Donnie and Arlen both recalled meeting east coast painter Dave Perewitz in Detroit—it wouldn’t be the last time, either.

Arlen said the Detroit show was a real eye opener. He’d had bikes featured in magazines for a couple of years by then, thanks to Larry Kumferman, editor of Custom Bike. And though it was the first time he actually got paid to attend a show (“It was a big deal. I got a plane ticket and a hundred bucks!”) he wasn’t prepared for the reception he received. “There were quite a few people that wanted to meet me. I was shocked and surprised about that!” said Arlen.

Just a few years before then, Arlen was painting bikes and had designed a few parts. In the early ‘70s aftermarket motorcycle parts were in demand and tough to get from the few companies making them—AEE, CJ Custom Cycle Parts, Santee, Drag Specialties.

“You couldn’t get ramhorn bars,” said Arlen. “So I went to a tubing bender, then I welded it and took it to the chrome shop. That was my first product.” Next was a rear fender with built-in taillight. “I made it in steel then made a fiberglass mold and we started making rear fenders.”

Feature articles in magazines got the parts noticed. “People would call after they’d seen the magazine and want to buy the part. We didn’t know it then but we were building our brand,” he said. How did they spread the word? “Our first catalog was one sheet of paper that Bev typed up. It didn’t even have a picture!”

As Arlen’s product count increased he considered finding a distributor and went to see Gary Bang, who gave him the best advice of his young career. “He told me, don’t show these products to other people, they’ll copy you. First get your pricing structure right.” So Arlen educated himself on manufacturing and applied what he learned to continually refine the process.

Arlen also reached out to racer and builder Jim Davis. “I took a stock Sporty frame to his shop. We laid it on its side and I drew around it in chalk, extending it in the front and back and so on. He actually made the first frame for us working off the chalk marks on the cement.”

Seeking out experts and learning from the best paid off. “I think that was one of my secrets,” said Arlen. “I always aligned myself with quality people, smart people. I paid more than anyone else but I always had good, safe products. That had a lot to do with our success.”

It took time but he ultimately developed a network that made it possible to offer a selection of cool, clever components. “The more neat stuff you made the more people wanted to do things for you,” he said.

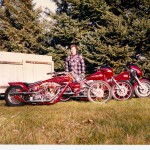

Going to the major events like Daytona and Sturgis was important then and it became common for Donnie, Arlen and Dave to hang out together. You didn’t have a booth in those days, you just brought your bike, rode it around and showed people. In 1977 they were at the Rat’s Hole Show in Daytona. “Dave had that thing locked down, and it was fun” said Arlen. At the time Dave had never been to Sturgis so Arlen talked him into going. “I’d already been to Sturgis several times and had met Donnie there before. So we all hooked up in Sturgis that year.”

Compared to Arlen and Donnie, Dave was the youngster, the go-getter from the east coast. And it took grit and ingenuity to get noticed—the custom bike business out east was not as refined as in California. “We’d run to the book store every month to get a magazine because that was the only source you had,” said Dave. “It was pretty much trial and error.”

Looking at a new issue of Custom Bike sometime in 1974, Dave got the idea that the bikes he was building and painting were magazine quality, so he picked up the phone, got editor Larry Kumferman on the line and told him so. Two weeks later, Kumferman flew to Massachusetts to photograph Dave’s bikes, starting a run of publicity that continues still.

Early the next year, Dave learned about the “It’s Called Detroit” show, as he explained: “We threw bikes in a van and drove thru a snowstorm in March to Detroit. When we got there Larry was shooting the show and he introduced me to Arlen.” Dave met Donnie there, too. By the end of the weekend Dave had invited Arlen to Laconia that summer and Arlen accepted. “He shipped his bike and flew out, and we spent the week in Laconia. After that he said, listen, I know these guys in Detroit, why don’t we go to Detroit? So we threw the bikes in my van and went to Detroit. We spent a week riding there with Yosemite Sam, Carlini, Finch and slept on the floor at Sam’s house. Then Arlen invited me and Donnie out for the Oakland Roadster show and we’ve all been best friends ever since.”

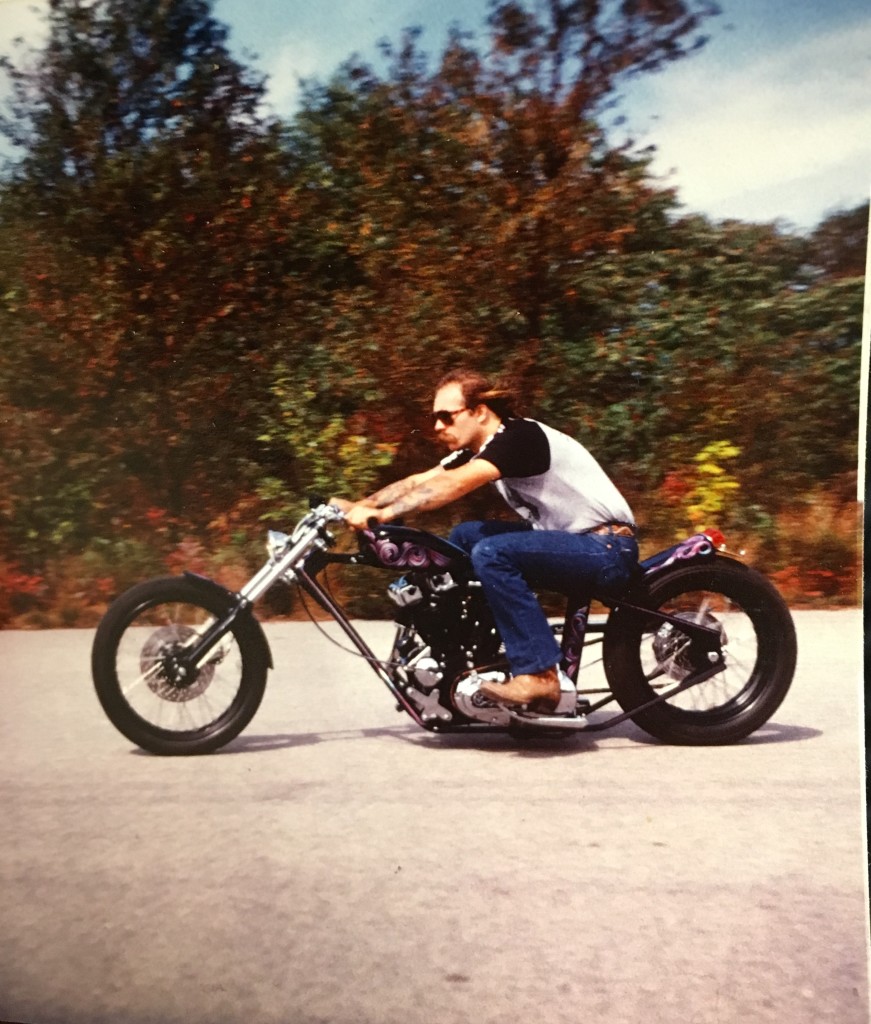

Dave recalls that first trip to Sturgis well. Arlen brought him a bike to ride, a Sportster digger, of course. “That’s what we were all riding back then,” said Dave. “We stayed at City Park and it was pretty crazy. We were up all night while guys were drag racing in the street and doing burnouts.” He didn’t need to be talked into going back.

Even among like-minded people there’s no predicting the future, and this would be a good story if friendship had been the only result of a couple of chance meetings over 40 years ago. But lucky for riders everywhere, the rapport between Smith, Ness and Perewitz not only established custom biking in America but their passion for the subject continues to sustain it. That gives the story way more horsepower.

Custom Styling Cues circa 1975

Some say everything’s derivative. Read on and you might be convinced that there’s still room in the world for creative genius.

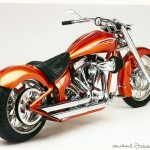

Arlen Ness • West Coast

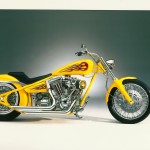

“I always liked drag bikes, the racing look. Long and low and performance looking. Some people called them diggers. Then I started making those fancy diamond gas tanks and coffin tanks, that kind of stuff. Then flat bottom Sportster tanks for the Sportster diggers. In the early days we did quite a bit of stuff that nobody had ever done.”

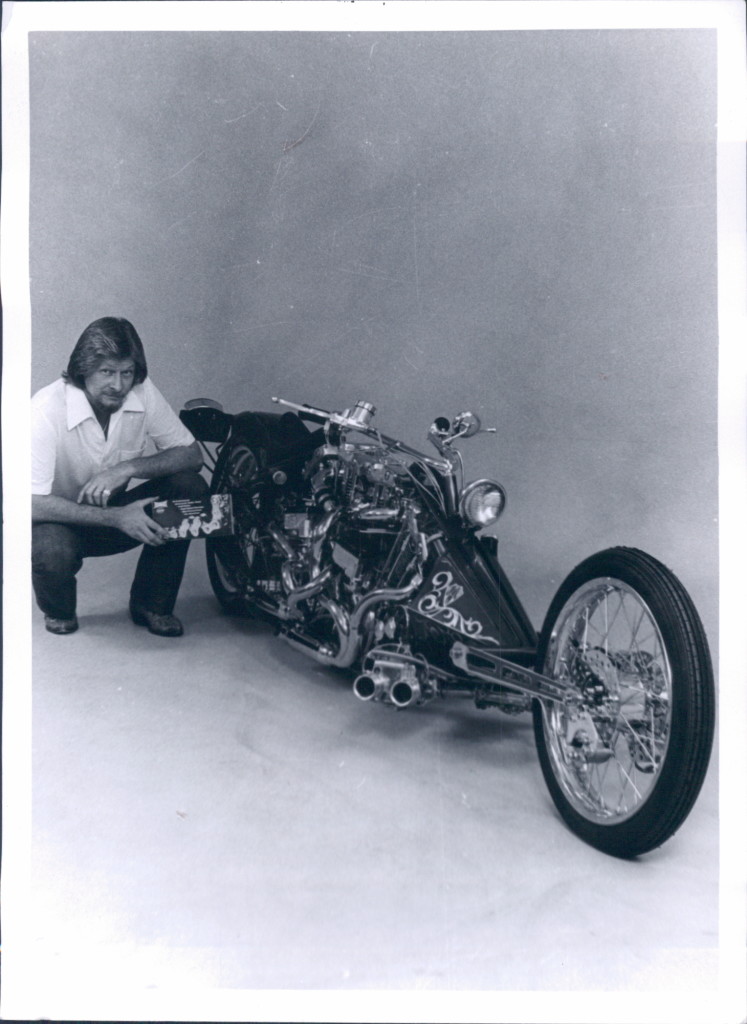

Donnie Smith • Midwest

“We built a lot of bikes that had 16-over front ends, that seemed to be a thing for a couple of years. We would extend the frame but we would always slide the gas tank back, right to the seat. Other guys like Arlen used to sit their tanks out in the middle of the tube. We’d put little wings or fins on the front of the tank to blend it into the front of the fork. That was our look for a long time.

“We were a little more practical, we needed more gas to ride further. So I designed a tank that held close to 3 gallons. It had a long prismatic look that was big in those days.”

Dave Perewitz • East Coast

“Arlen had started the whole digger look of styling, the Ness style, and I was pretty much the first guy who started doing that on the east coast. My stuff was rigid frame, Sportster tank mounted high, 6-over front end with a raked frame. And I paid attention to the paint, too. When I first started painting there were a couple guys around who did candy paint on cars but that was the extent of custom paint on the east coast!”

More Stories

BJ Emerson’s 1972 Triumph T100R Custom Chopper 🇬🇧

Ride Moonshiner, Rattler, Blue Ridge Pkwy 🏍️

Indian Motorcycle Releases Third Episode of Scout Custom Series